Rob Dassie had only heard the rumors.

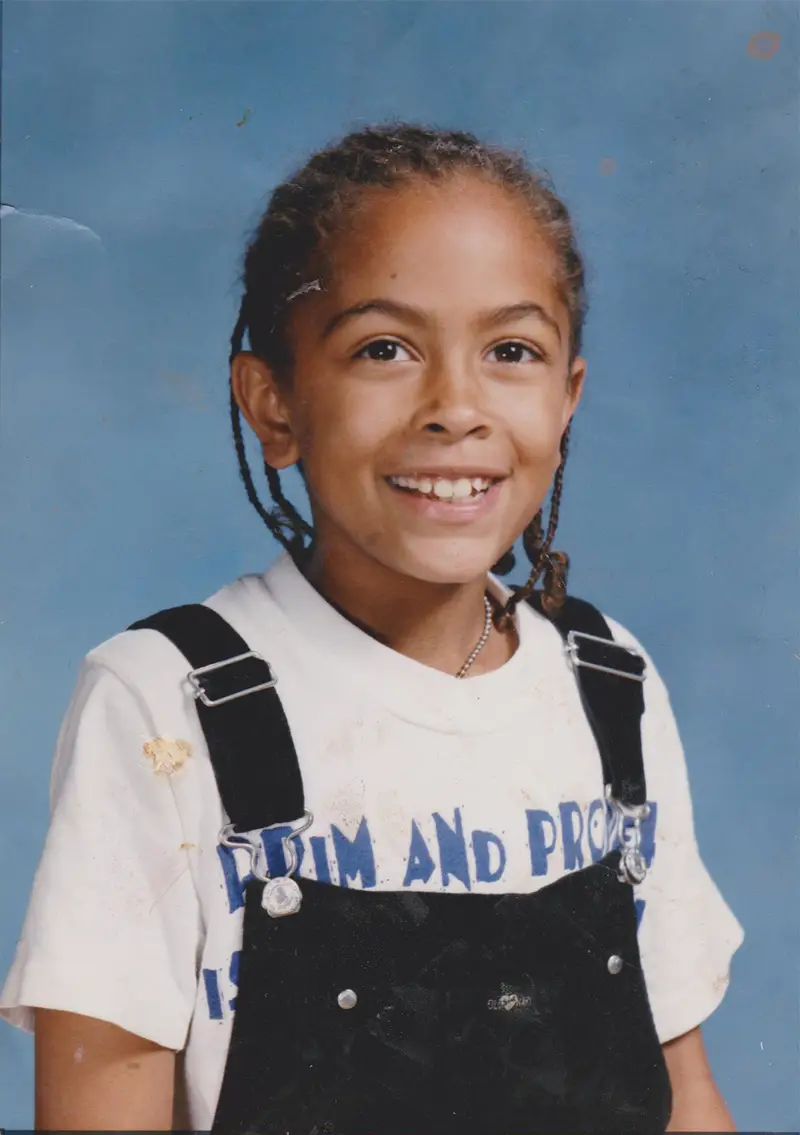

An 8-year old basketball prodigy had just moved to Kingston, N.Y. She could shoot with pinpoint accuracy and dribble two balls at once. And she practiced just down the block from Dassie’s gym.

He had to see the girl that everyone was talking about. He had to see Rachel Coffey.

So Dassie invited her to the Rondout Center, handed her a ball and though she was a short, skinny, hair-braided little girl surrounded by teenage boys, he challenged her.

“Let’s see what you can do,” he said.

It didn’t take long for Rachel to validate everything that Dassie had heard about her.

She walked out onto the court where all of the older guys were playing and did what only she knew she could do.

What started out as just Dassie watching from the sidelines turned into a spectacle for the entire gym.

She made more shots than the older guys. The older guys were probably about 15, and she was making all their shots.

Rob Dassie

“That was my first impression and I was very impressed with her basketball skills, her feel for the game and how much she loved basketball at that young age.”

In her hometown of Kingston, everyone viewed Rachel the way Dassie did — as a basketball star.

In reality, basketball was simply her escape.

“It was the thing that kept me on track,” Coffey said. “It was one thing that just motivated me and it was really important in my life.”

Growing up, there were a lot of things that could have taken Coffey off track.

When she was just 5 days old, she was adopted by Lorraine Coffey, only to be taken back three months later by her biological mother, Marie Bradford, who used drugs during her pregnancy. Then 5 months later, she was given back to Lorraine.

Rachel survived a potentially life-threatening skin infection, moved homes three times, lost an influential former teacher, grew up in a household with nine siblings and went through school with a suspected learning disability.

So while her surroundings were always changing, basketball was the one constant.

Now a senior at Syracuse, basketball remains the anchor in her life. She’s the starting point guard on a team preparing for its second NCAA Tournament in as many seasons.

Courtesy of the Coffey family

When Lorraine Coffey adopted Heather Bradford, the Coffey family changed her name to Rachel.

But three months later, because it was a risk adoption, Marie Bradford, Rachel’s biological mother, was able to take her back.

And when she was back in Bradford’s care, Rachel was neglected. She was put inside a crib for two straight weeks. Her clothes were never changed. She spent nearly every moment in her crib crying.

“It’s frustrating that you could do that to a child,” Rachel said.

Bradford eventually gave Rachel back to Lorraine, but she wasn’t the bubbly baby the family had been forced to give up just months earlier.

Rachel would sit in her crib awake and never cry. She’d lost the capability to do so. She had scabies, a skin condition, and Rachel’s doctor said hers was the worst he had ever seen. She’d rub her wrists and ankles together to combat the itching sensation that covered her body.

She'd wake up and we'd be right there at the crib, and then she would just make a whimper. Eventually she saw that were were coming for her when she'd make a sound, and then she was able to cry.Lorraine Coffey

But as Rachel grew up, she took a circumstance that many might let get the best of them, and made the best of it. Though she didn’t live with her biological parents, she grew to view Lorraine and her husband Patrick as her true parents. Her nine siblings, three of which were also adopted, were brothers and sisters.

And because she had a supporting family, she was able to find her true passion on the basketball court.

As she grew older, her streetball skills turned heads and her crossovers left many victims on the ground as Rachel raced to the rim.

Courtesy of the Coffey family

From Rachel’s perspective, little had changed in the family dynamic as she grew older. But at the age of 11, Rachel was alone in a divided household.

Lorraine and Patrick were getting a divorce, and everyone was taking their mother’s side, except Rachel, the youngest. She didn’t see her father’s error like everyone else.

Rachel just saw her daddy, the man that came to her basketball games and loved her more than anyone else in the world.

“They were able to see that daddy wasn’t doing the right thing and daddy wasn’t coming home,” Lorraine said, “and daddy wasn’t being daddy like he usually was. Rachel, she was younger, and she was more like daddy’s little girl.”

Courtesy of the Coffey family

Even after the two split up, Rachel would go over to her father’s house every day.

At home, the scene was more chaotic. There were nine siblings and a mother that worked around the clock.

“We were in the ‘hood, and then our dad moved out, it was difficult adapting, and it was difficult not having your dad around anymore,” Rachel’s older sister Esther Coffey said. “My mom was a stay-at-home mom, and for her to go to work and work overnights, it was a big adjustment.”

Esther became the de facto mother when Lorraine wasn’t home.

When Lorraine was at work and couldn’t bring Rachel to basketball practice, Esther did, and it allowed her younger sister to continue excelling on the court.

Courtesy of the Coffey family

Near the start of Rachel’s senior season at Kingston High School, Syracuse head coach Quentin Hillsman presented her with a very serious problem.

She needed to get her grades up or she wouldn’t be able to play for him.

School had never been Rachel’s strong suit, nor her greatest interest. She suffered from a learning disability as a result of the drugs her birth mother used, Lorraine said.

But her seventh grade teacher, Valerie Simmons, took it upon herself to make sure Rachel did well in school.

Rachel would spend afternoons in Simmons’ office talking about life. Simmons helped Rachel with all of her schoolwork and went to all of her basketball games.

After Rachel graduated, Simmons would come up and visit in Syracuse and knew the entire SU basketball team.

“She never had children, and Rachel became the daughter she never had,” Lorraine said. “It was something that they fulfilled in each other. There was a need there that Rachel had and there was a need there that Valerie had, and they fulfilled it in one another.”

An elderly Simmons died on Feb. 19, 2013. When Rachel heard the news, she didn’t know how to process it. She had a game that night against Rutgers, and scored a season-high 17 points in an eventual Syracuse win.

Simmons meant everything to Rachel. She has a tattoo of Simmons on her arm, and remembers her teacher making time for her when nobody else would.

“It helped a lot, because school was never my interest,” Rachel said. “It helped a lot to see somebody to put that much effort and want me to do good.”

When Kingston head coach Steve Garner announced the honor roll at the end of Rachel’s senior season — a group that Rachel had poked fun at in previous years — this time, she was on it.

“Once I found out I couldn’t play, it motivated me to go,” Rachel said. “Basketball is one of the only things that could motivate me. Because if you told me I couldn’t play, I’d go study for a test.”

Courtesy of the Coffey family

It was the same calm and level-headed approach that Rachel took when she first saw the name Marie Bradford appear in her Facebook inbox.

All then-18-year-old Rachel read was the first part of the sentence.

“Hi. I’m your mother.”

Once she saw the name, she knew who it was and ran downstairs to find Lorraine.

Bradford, her biological mother, had just contacted Rachel for the first time. Bradford had lived in Kingston all of Rachel’s life and Rachel never knew. It came as a shock and surprise to her, but it gave them an opportunity to meet.

Rachel went to the salon where Bradford worked and waited for her mother to come out from the back of the shop.

A few minutes later, Bradford emerged. It was the first time Rachel had seen her biological mother since she was a baby. But for Bradford, the moment was too much.

Without a word, she retreated into the back of the store once again.

I wanted to tell her that I did forgive her, and that I was thankful for what she did. But it's also kind of hard for her as a person, she still didn't get over it. She's going through a lot.Rachel Coffey

Since then, the two have met a few times, but haven’t sustained a relationship. And Rachel’s OK with that.

Under Rachel’s bed is a scrapbook. One section holds mementos from her childhood. Her birth certificate with a different name, her old benefit card. On the other are newspaper clippings and photos commemorating her basketball career.

It shows where she’s been and what’s she’s become. It’s a story of her history, and how she overcame it.

It’s not something that she looks at often. She doesn’t need the reminders.

She could have folded every step of the way, but there were always people there for her.

And there’s always been basketball.

Banner photo by Emma Fierberg | Asst. Photo Editor

Published on March 18, 2014 at 2:38 am

Contact Sam: sblum@syr.edu | @SamBlum3

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Great story and I’ve been to a few games to bring my little sister and they love Coffey and her skills on the court

I enjoyed the times at the YMCA watching her outperform her male peers on the courts.

I grew up with Rachel’s Dad’s family, they were a loving family with all the trials of big families! Her Aunt Teresa and Donna were my childhood friends. It’s nice to see you with your Dad in the old photos! Congrats on making a success of yourself! Never stop believing!