Syracuse University plans to spend millions to upgrade Archbold Gymnasium, following a nationwide trend in spending

Katie Reahl | Contributing Photographer

As part of Syracuse University Chancellor Kent Syverud's Campus Framework plan, Archbold Gymnasium will be renamed "The Arch."

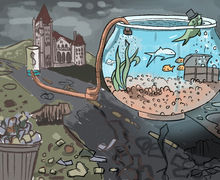

It’s one of the most high-profile trends in higher education spending.

Colleges across the United States have been raising millions of dollars to upgrade recreational centers in hopes of attracting more students in an increasingly competitive marketplace, experts say.

Wake Forest University, an Atlantic Coast Conference school, spent $58 million on rec center renovations this past year.

In 2011, Louisiana State University drew national attention after the Student Union voted to charge students a rec fee to fund the construction of a lazy river, rock climbing wall and ropes course, among other things. LSU’s project cost about $85 million in total.

Cornell University, a Syracuse University peer institution, recently spent $850,000 to upgrade its climbing center. That project wrapped up last year.

Now, SU is joining that trend as officials prepare for a multimillion-dollar upgrade to Archbold Gymnasium.

“I guess you can call it, and others have called it, an arms race to attract students,” said Steven Hurlburt, a senior researcher at the Delta Cost Project. “Students expect these high-end dorms and dining options and recreational facilities.”

University officials have said that, as part of Chancellor Kent Syverud’s Campus Framework plan, Archbold Gymnasium will be renamed “The Arch.” The building will be expanded by an additional 7,000 square-feet in space. It will feature a new multifloor fitness center, rock climbing wall and “multi-activity sports court.”

A rendering of The Arch from the Campus Framework.

Courtesy of SU

No concrete construction timeline has been released for the project. Pete Sala, vice president and chief facilities officer, last year said the university hoped to finish Archbold improvements by fall 2018. SU previously estimated the project would cost about $50 million.

“Particularly in the Northeast and Midwest, you’ve got a declining student population coming out of high school, and as a result, you’ve got to be competitive,” said James Kadamus, a senior adviser at Sightlines, a Connecticut-based education consultant firm.

Colleges have to consider the possible financial benefits of investing in luxury recreation centers, Kadamus said. And, the possible financial pitfalls.

Sightlines found that many university gyms and recreation centers were built decades ago. Upgrades are needed, Kadamus said. Aging infrastructure, coupled with students who prioritize luxury student amenities, push officials to invest more in recreation centers, experts say. Archbold Gymnasium is more than 100 years old.

Since 2007, the amount of money invested in existing capital space has averaged $5 per gross square foot, not adjusted for inflation, according to a 2016 Sightlines report on college spending. Investment levels dropped below that average in 2010-11, following the Great Recession, but rebounded to nearly 2009 levels by 2015, per the report.

Tuition is typically not affected by these types of projects, Hurlburt said, because universities foot the bill through rec fees or fundraising campaigns.

But elaborate recreation centers can pose a public relations challenge, as tuition continues to rise nationally and officials spend millions on projects such as lazy rivers, ropes courses and climbing walls, experts say.

Andy Mendes | Digital Design Editor

A report published by the Delta Cost Project, co-authored by Kadamus, in 2012 found college rock climbing walls, on average, cost $100,000 or more. Those headline-grabbing endeavors only account for a small portion of total recreation project costs, though. Heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, electrical wiring and new roofing are more expensive, Kadamus said.

“See what your student body is like. What they want, do they use it?” Kadamus said. “If it’s going to be something that helps attract students, I support it wholeheartedly. If it’s something that some students might not get as much use out of, or you don’t have a big student base to split the cost, I think you really have to be cautious about it.”

At LSU, students now pay $200 a semester in rec fees. The rock climbing wall is open. A lazy river loops around in a small pool area to form the initials “LSU.”

Jason Badeaux, LSU’s student body president, said the project has proven successful. The recreation center is a major hub on campus. Badeaux recently went climbing there.

“It’s been a huge factor in getting students to the gym and living a healthy lifestyle,” said Badeaux, a junior at LSU. He was not involved in the 2011 Student Union vote to implement rec fees, but said the project was not controversial at the time.

Archbold Gynmasium as it stands today. Renovations will cost an estimated $50 million.

Katie Reahl | Contributing Photographer

Unlike other colleges, SU will not charge students an extra rec fee to pay for its major project, said Sarah Scalese, associate vice president for university communications, in an email. Instead, SU will focus on private donors.

A “health and wellness fee,” already included in costs for full-time students, will also help fund the project, Scalese said. Students pay about $700 in health and wellness fees each year. Those fees, at present, help support the Counseling Center and other programs.

Matt Ter Molen, the university’s chief advancement officer, on Monday said SU is making progress in Arch fundraising efforts. Steven Barnes, president of SU’s Board of Trustees, along with his wife, Deborah, donated $5 million to the project this summer.

In the next two to four weeks, another multimillion-dollar gift will be announced in support of The Arch, Molen said.

Initial renderings for both LSU’s rec project and The Arch noted an elevated running track that loops throughout buildings. James Franco, SU’s Student Association president, said The Arch will transform campus by consolidating health service programs in one building.

“It can’t not,” said Franco, when asked if the project would help SU recruitment.

Research is mixed, though, on whether colleges actually enhance recruitment efforts by investing in major recreational projects such as The Arch. The National Bureau of Economic Research, in a 2013 study, found a positive correlation between amenity spending and improved recruitment.

But economists at Wake Forest and Colorado College also, that same year, found college reputation may play a bigger role in recruitment than academic and nonacademic amenity spending.

“I guess the jury is still out on whether this is actually an effective approach,” said Hurlburt, the Delta Cost Project senior researcher.

Published on October 12, 2017 at 1:21 am

Contact Sam: sfogozal@syr.edu | @SamOgozalek