‘The MacGyver’: Here’s how Rex Culpepper can put together SU’s broken pieces

Max Freund | Staff Photographer

Rex Culpepper has the intelligence and intangible qualities to piece together Syracuse’s broken offense.

The Daily Orange is a nonprofit newsroom that receives no funding from Syracuse University. Consider donating today to support our mission.

Robert Weiner’s mahogany, 25th-anniversary edition Taylor acoustic guitar, the one he calls his baby, sits in Rex Culpepper’s Aspen Heights apartment. It’s gotten much more use there than it would’ve back home in Tampa, Florida.

Weiner, Culpepper’s high school coach, bought the top-of-the-line instrument years ago, hoping he’d guilt himself into learning how to play. He never picked it up, but his quarterback fell in love with what turned into a graduation gift. Only Culpepper could possibly take care of his “baby” — there’s no one in college football quite like the guitar-strumming, motorbike-riding, death-defying Culpepper.

Along with guitar, Culpepper plays the piano by ear and once put on an impromptu Christmas carol concert in the Atlanta airport during a delayed flight. He repairs motorcycles and operates his own garage in Syracuse, and taught himself the ins and outs of the stock market during the lockdown.

His parents finished second in the reality TV show “Survivor,” his dad Brad played nine seasons in the NFL, and his next-door neighbor is Tom Brady.

And at age 21, he beat testicular cancer.

“There’s so many different things that make him up as a young man,” Weiner said. “That’s what’s kind of intriguing about him, and really a once-in-a-lifetime person to be around.”

With Tommy DeVito sidelined for an uncertain period of time with a left foot injury, Rex is Syracuse’s starting quarterback for the foreseeable future. Weiner called him the brightest student in all of Florida, and Syracuse head coach Dino Babers said he’s one of the smartest people he knows. He hasn’t been a full-time starter since his junior year at Plant (FL) High School — and the years since then have been filled with physical setbacks — but if Rex succeeds under center, it’ll be because he’s used his mind to piece together the scattered parts of Syracuse’s offense.

“Rex is not normal,” Babers said. “Rex is not average.”

• • •

As her son skipped down Heinz Field in Pittsburgh, shouting and shooting his double-fisted arms up in celebration after Syracuse’s first touchdown of 2020, a tear rolled down Monica Culpepper’s cheek.

On the second snap after replacing an ineffective DeVito in Syracuse’s Week 2 matchup, Rex caught the shotgun snap, twirled it once in his hands and floated a pass 69 yards down the right sideline into the arms of a streaking Taj Harris.

Rex goes up top to Taj!

Watch live on ACCN: https://t.co/c9m7xA1Plz pic.twitter.com/hDWDT2jjyV

— Syracuse Football (@CuseFootball) September 19, 2020

“Rex’s touchdown meant so much to Syracuse and the football, energizing them, but it meant so much more to just see our kid incredibly happy,” Monica said. “Because when your kids are happy, you’re happy.”

About two years prior, in March 2018, Rex was returning to Syracuse from a vacation in Iceland when he noticed one of his testicles was swollen. An ultrasound confirmed he had testicular cancer, and he later learned it had spread to his lymph nodes.

Back home in Tampa, doctors at the Moffitt Cancer Center told Rex his condition was treatable, that there’s a 98% cure rate. Through his 100 hours of chemotherapy over 10 weeks, Rex lifted weights to stay in shape with whatever energy radiation didn’t sap out of him. A month into his treatment, he returned to SU and slung a 17-yard touchdown in a spring game.

Three days after that spring ball highlight, though, came a scare. Back in Tampa for his second round of chemo, Rex had an allergic reaction to a mixing agent used in his treatment, according to Syracuse.com. Doctors rushed to his aid. He later told his coaches and teammates in an award acceptance speech that he thought his “life was out of my control.”

Cancer can't stop @CuseFootball QB Rex Culpepper from slinging TDs! #RexStrong #MustSeeACC pic.twitter.com/FqjkmHjYnd

— ACC Digital Network (@theACCDN) April 14, 2018

Rex’s relief performance against Pitt was his first meaningful playing time since the diagnosis, but it didn’t jolt SU enough to come back, and it wasn’t enough to earn him the starting job. He finished the game 4-for-9 with 88 yards, but the highlight touchdown was still viewed hundreds of thousands of times on social media and featured on ESPN’s Scott Van Pelt’s “Best Thing I Saw Today.”

His 100 hours of chemotherapy — represented by individual tally marks tattooed on his right rib cage — his weight training between treatments and his long nights in the Moffitt Cancer Center were in the past. He had been declared cancer-free in June 2018, and his once bald head now featured an outgrown, curly mop.

“It’s easy to let your whole world kinda collapse on you,” Rex said in a video posted by the Moffitt Cancer Center. “Instead of feeling sorry for yourself that you’re going through the treatment, I don’t see this holding you back at all. I want to compete for the starting quarterback job just like this never happened. Apart from that, I’d just like to be somebody who another athlete who’s unlucky enough to get testicular cancer can look up to.”

Yiwei He | Design Editor

Those around Rex say the energy he plays with, and the joy he lives with, comes from the perspective he gained from not only his cancer battle, but also a torn ACL he suffered before his senior year of high school. His father said his maturity level is more like a 50-year-old than a 22-year-old.

“We’re ready to turn the page,” Brad said days after the Pitt game.

• • •

In Rex’s first high school start as a junior at Plant High, Weiner trusted him to call plays. He’d never done that before with any quarterback, let alone one in his first start. Then again, he’d never coached someone whom he thought was the smartest person — not just football player — in the state.

“I knew that the biggest asset we had was his intelligence,” Weiner, now offensive coordinator at Toledo, said.

It was a 2014 preseason game versus Plant’s arch-rival, Armwood, which featured the best defensive tackle in the class, Byron Cowart. Before every snap, Rex had five reads to determine which play to call, Weiner said. His numbers that game were “very pedestrian,” Weiner said — he probably didn’t even crack 100 yards. But Weiner said Rex got Plant into the right play call every down, which allowed running back Patrick Reed to rush for 165 yards. For the rest of the season, Armwood allowed 385 total rushing yards, Weiner said.

Much of Rex’s play-calling entailed staying away from Cowart, who finished with just one assisted tackle, Weiner said. In the postgame handshake line, Rex and Weiner met Cowart.

“’Y’all are scared of me,’” Cowart told them.

“’You call it scared. We call it smart,’” Weiner replied.

But in the locker room, Rex sat disappointed with his head in his hands. Even though his team pulled off the upset, he was frustrated with how he played, embarrassed even.

One month into his cancer treatment, Rex Culpepper returned to SU and threw a touchdown in its spring game. Max Freund | Staff Photographer

“No, Rex,” Weiner said. “You have no understanding of what it is to beat Armwood and what you did to help us get there. We don’t win if someone else is the quarterback of that game.”

That was the beginning of a season in which Rex’s stock skyrocketed. The now 6-foot-3, 225-pound pro-style QB became a 3-star prospect and earned the attention of Syracuse, Miami, South Florida, West Virginia and Florida.

Entering his senior season, Weiner and Rex could focus on honing his throwing mechanics, since his football mind was so advanced. Rex had put it all together, and Weiner expected him to be the top quarterback in Florida.

But then, during a 7-on-7 tournament in the summer before his senior season, Rex tore his ACL playing receiver. Letting Rex play in that meaningless game was one of the lowest moments of Weiner’s coaching career, but he said Rex’s rehab process served as a “warmup as to how to handle something difficult.”

Instead of leading Plant behind center, Rex became Weiner’s de facto offensive coordinator.

For Plant’s first game of the 2015 season, Rex’s younger brother Judge, now a defensive tackle at Penn State, was in at quarterback. From the sidelines, Rex noticed Venice’s safety kept crashing down into the box. He then told Weiner to call “Dewey Gator,” one of Plant’s simplest but most effective actions in the playbook. It involves a slot receiver running a double move, faking a curl and then running up the seam.

The safety took the bait, and Judge tossed an 84-yard touchdown. Just like his brother drew it up.

• • •

When Babers walked up to the Culpeppers’ home on Davis Islands, a neighborhood on the Hillsborough Bay, he quickly realized his backup quarterback was different. It was the winter of 2015, shortly after he signed on as Syracuse’s head coach, and he first noticed Rex outside his house in a dune buggy.

“Wow, that’s a nice thing. Where’d you buy it?” he asked Rex. Then Brad interrupted — no, Rex built it from the ground up.

Rex has a habit of making something out of nothing. Almost every piece of furniture in Plant High’s quarterback office — the shelves, bookcases, desks — were handmade by Rex. In between summer training sessions, Rex would go out and buy materials and work on crafting the room, styling it as he envisioned.

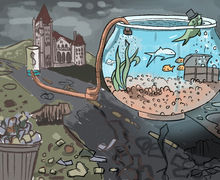

“I always call Rex ‘The MacGyver,’” Weiner said, referencing a 1985 television series about a genius engineer and crime-solver.

“He’s the guy who you give him a paper clip and give him a pencil and give him a piece of paper and he’s going to create a boat engine out of it. Use a magnifying glass to start an ignition and get something to go.”

Katelyn Marcy | Digital Design Director

But at Syracuse, where he graduated last spring magna cum laude from the Newhouse School of Public Communications, Rex hasn’t had much of a chance to put things together on the field. He redshirted his freshman year, still recovering from his torn ACL. Then he served as Eric Dungey’s backup for two years, attempting 75 passes in 18 appearances.

Even with the lack of playing time, Rex never seriously entertained transferring, his parents said. He remained loyal to a program and a school he loves, they added. As a backup, Rex remained patient for his chance, something he learned from his time rehabbing and in chemotherapy.

“What we think is most admirable about Rex is his perseverance,” Monica said. “I think that cancer at a young age like that, and 100 hours of chemotherapy, changes your perspective on a lot of things. You don’t really harbor the negative. You don’t be bitter. You just look forward to what’s next.”

With DeVito out, the “next” is now. Babers said Rex knows the playbook as well as anyone, but since the 69-yard touchdown versus Pitt touchdown, Rex has passed for just 44 yards on 18 attempts and an interception.

In high school, he’d study the mechanics of his receivers, watching their hips to know when someone’s going into a cut or taking an option route, Weiner said. But this year, Rex’s timing with his receivers has been off, particularly on throws to the outside.

And with 10 key players injured at the moment, the pieces of the Syracuse offense around Rex appear broken. SU doesn’t have much of a choice but to hope Rex can put them together.

Published on October 13, 2020 at 11:28 pm

Contact Danny: dremerma@syr.edu | @DannyEmerman