Loud house legacy: After 33 years, Carrier Dome evolves into SU icon

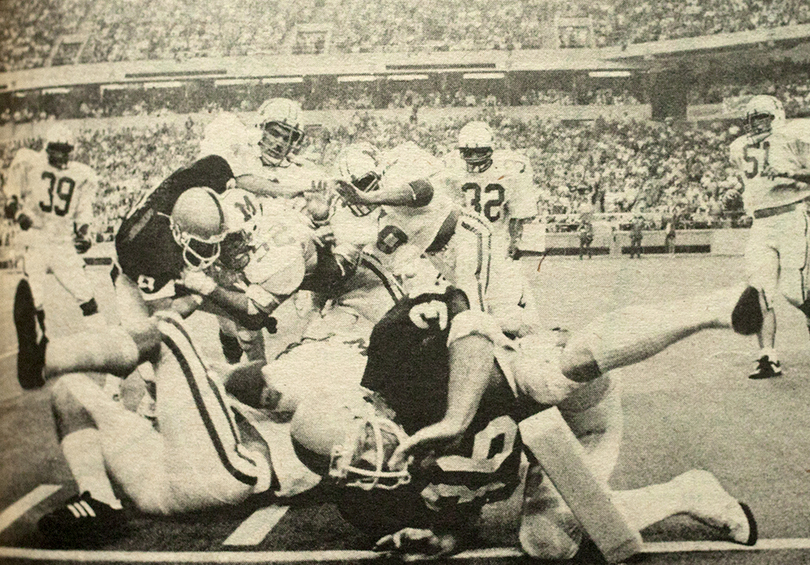

Agony, elation, pride, noise — all are elements of Syracuse University Athletics that are amplified by the Carrier Dome.

The Dome has come to serve as the epicenter of sports fanaticism at SU. Much like its predecessor, Archbold Stadium, it has also become a symbol of the school’s athletic programs. Now, 33 years later, the university and the Dome have entered the Atlantic Coast Conference hoping to continue the tradition it established in the Big East Conference.

The Dome was built to replace Archbold Stadium, an aging Roman coliseum replica that hosted the university’s football games. When the basketball team played at Manley Field House, Boeheim was reluctant to move to the Dome, since it would mean leaving the facility where the Orange had enjoyed a winning streak.

Through the years, Archbold racked up fire code violations. The Syracuse Fire Department eventually reduced the stadium’s maximum occupancy from 40,000 to 26,000.

The question of what to do with Archbold reflected a deeper issue about Syracuse’s ambitions for its football program, said Ira Berkowitz, a 1982 alumnus and president of the Syracuse University Northern North Jersey Alumni Club.

Even at a 26,000-person limit, Archbold was rarely full, he said, calling the stadium a detriment to the football program.

“At this point, Syracuse University had to make the decision as to whether they were going to continue to play big-time college football or go down to the next tier,” Berkowitz said. “It was that close.”

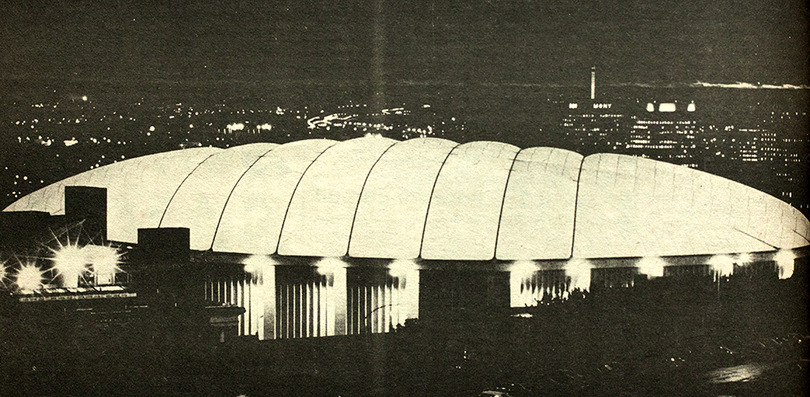

Syracuse chose to level up: Construction on the Dome started in 1979. New York Gov. Hugh Carey poured $15 million in state money into the project, calling it a public-private partnership.

Air conditioning giant Carrier Corporation bought eternal naming rights for $2.75 million, one of the first of its kind in the country. The Dome cost $26.85 million in total.

Pre-construction engineering studies tracked air flow through the stadium design, Berkowitz said. The main sections of the stadium lack air conditioning — an irony meant to compensate for Syracuse winters.

The air flow studies forgot to account for body heat.

At his first game at the Dome, Berkowitz said, a thin, translucent fog coated everything inside — condensation from the warm air and heat radiating off tens of thousands of bodies.

Not considering fans’ body heat is a “surprisingly common” environmental engineering flaw, said Benjamin Flowers, an associate professor of architecture at the Georgia Institute of Technology who studies stadiums.

But overall, the Dome is a pragmatic building with function taking precedence, Flowers said. “What was important then was not what it looked like in the landscape, but how it operates inside.”

For the first half of the 20th century, Syracuse was in some ways a city in decline, he said. The massiveness of the Dome provided an urban identity for the city to rally around, Flowers said, speaking to a period when people were building on a big scale as a reminder of Syracuse’s greatness at one time.

The Dome represents the city’s switch from an industrial economy to one focused on sports tourism, Flowers said.

It’s this sports tourism that’s helped fuel a culture surrounding the Dome, specifically elevating men’s basketball head coach Jim Boeheim to a national figure in college sports.

When Big Boeheim, a giant cardboard cutout of Boeheim’s face, first showed up, it was in the Dome.

In 2010, Pat Manley, a 2011 graduate of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, was disappointed with a lackluster student section and wanted to do something outrageous.

During the 2009-10 season, Manley made two Big Boeheims — one for home games and the other to travel with during the NCAA Tournament.

“I brought the head to the Marquette game at the beginning of the semester and first held it up during Boeheim’s pre-game introduction— jaws were dropping all over the Dome and players were absolutely cracking up on the bench,” Manley said in an email.

The big-head craze caught on and soon other big heads were looming above the student section, he said. At the end of the season, he donated the original Big Boeheim to the Jim and Julie Boeheim Foundation, and took the other with him to Washington, D.C., where he now lives.

Because of Syracuse sports fans, the Dome has become more than just a building, Manley said.

“Syracuse sports are an escape from the long, brutal winters of Upstate N.Y., and I think that’s why people flock to the Dome for basketball and football games,” Manley said. “In the two to three hours that you’re inside the Dome, you forget about the gray skies, sub-zero temperatures and punishing blizzards that are waiting for you outside. All that matters is a Syracuse win.”

The atmosphere in the Dome has always been electric, Manley said, but the athletic program’s recent success has helped it intensify. During his first year of graduate school, Otto’s Army, the SU student section, consisted of a handful of students camping out for basketball games.

Now, he said, there are hundreds.

The appeal of Syracuse sports is tied to the Dome, said Sean Keeley, a 2000 graduate who runs the blog Nunes Magician.

To Keeley, the sports at SU have a “very soap opera quality” – the football program with its ups and downs, the basketball team with recent controversy and Boeheim, an “interesting character study.” The unusually high expectations of Syracuse fans add to the drama, Keeley said.

“When Syracuse fans are excited about a program and the teams are doing well, they come out in droves,” he said. Fans are so invested in SU sports because it serves as one of the few national programs in the area.

“The Syracuse sports teams end up being a real identity,” Keeley said. Head football coach Scott Shafer said recently that he wanted his team to be hard-nosed because the people of Syracuse are hard-nosed, Keeley said.

The Dome, Keeley said, is essential to fans’ relationships with the team. It’s where most of the university’s sports are concentrated, like lacrosse and high-revenue programs like football and basketball. His favorite memories from college, he said, all took place in the Dome.

When Syracuse left the Big East, the switch raised the question of what will change going into the ACC. But Joe Giansante, SU’s executive senior associate athletic director, said any changes being planned for the Dome are part of the athletic department’s routine business and not specifically for the ACC.

One important result of moving to the ACC will be the increased revenue from competing in the conference.

The Dome is constantly being worked on, Giansante said. The athletics department is always looking for new ways to enhance the game experience for fans.

The point is to make sure that athletes from other teams leave the Dome thinking they’d left an “aggressive, incredible place.” As for SU’s move to the ACC, Giansante said that SU Athletics is hoping to rise to the next level in “all ways,” including facility-wise.

He disagreed with those who think the Dome is beginning to show its age. The building is iconic, partly because of an aura the basketball program helped create, and the household name. The Carrier Dome is one of the university’s greatest selling points with recruiting athletes.

Said Giansante: “There’s a wow factor when you walk in there. ”

Published on August 21, 2013 at 12:17 am

Contact Natsumi: najisaka@syr.edu